Autumning; v. the transformation of things in the natural world from their summer to their autumn selves.

Nan Shepherd wrote in The Living Mountain that when others talked the mountain – which was her constant companion and to which she was almost mystically attached – was silent. I’ve expressed a similar sentiment myself: to walk in solitude is best. And yet. Today we are companionable and quiet together as we set out into Strid Wood at Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale, letting the trees and the deepening cut of the ravine speak for themselves. Only occasionally do we interject our wonder. The russeting landscape does not need us to interpret for it; but occasionally wonder with the force of an electric charge asserts itself with the need to be stated aloud, as though in sharing it between ourselves we lay claim to our unified experience of this magic.

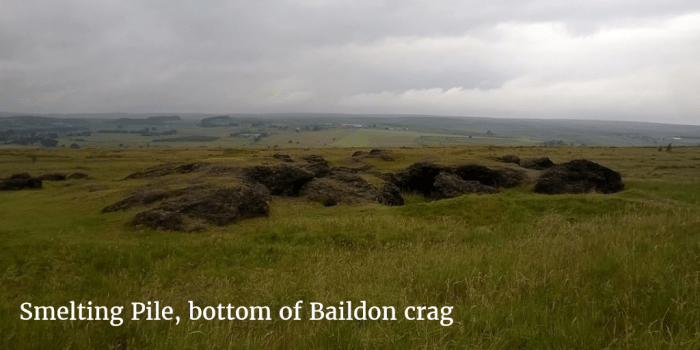

It is the morning preceding the autumn equinox and night and day exist in fragile and temporary harmony, split perfectly even like two halves of a ripening gourd, an uneasy truce until day starts its slow decline and we, grudgingly, will get up to darkness and our evenings will arrive with inky black before their time. Today we each walk with one foot in summer and one in autumn; looking forward and also behind. The outermost leaves of the crowns of the trees are flushed in eager reds: their chlorophyll gone, revealing their true colours. Those leaves further in are masked, for now at least, by their top-lofty canopies and are able to hang on to their green: summer’s final whisper. Sharp rot, leaf-decay, wood-smoke, the darkly astringent tang of fungi pushing up through the earth. We take the woodsy taste of it deep into our lungs, accept autumn is in the air and that summer has been lost until next year.

We do not do any of this deliberately; we are none of us aware that today marks the equinox until later reading an article about it – but our talk is preoccupied with the autumning of things: with the turncoat leaves, their deaths around us (and they do die brilliantly in this late-summer, autumn-precocious sun), and the chilling air that has brought a heavy sparkle of dew to the floor of the valley: silver underfoot.

The night has been cool and cloudless before us and I think to myself that the sunrise over the top of the valley will have been luminous as mother of pearl. The sun will have broken over the treetops in arcs of pale splendour and, for an exquisite moment, the night-dews will have borrowed its brilliance. The birds which noise to us now (the musical trilling robin, the shrilly barking crows that wheel overhead, the wagtails) must have started their cacophony of song in that thin morning light. A grey wagtail dips exuberantly in its distinctive flight over the sun-meshed water on our left. Happy to be about its day-flight; happy to be buoyed up on the autumn breeze.

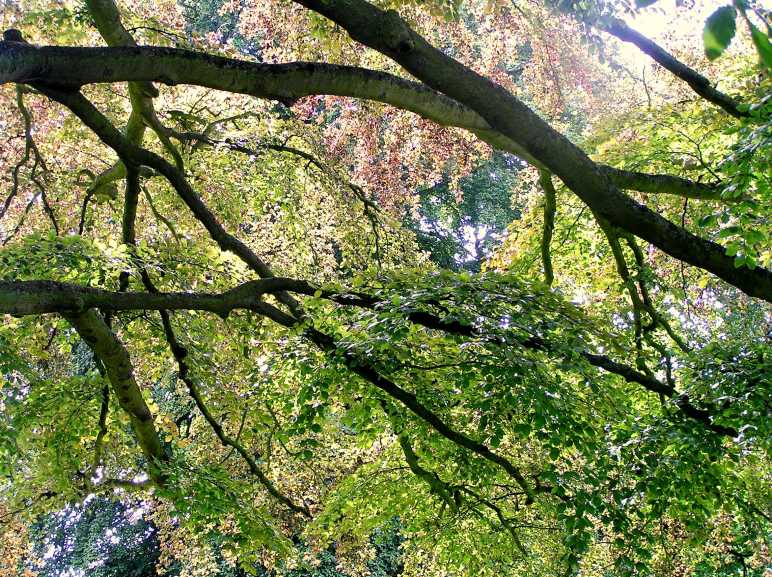

We are lucky that the sun has lingered to throw gold upon the changing trees before us; trees that clump together and march the sides of the valley, guiding us up through its mysteries. The sunlight is not constant but strikes here and there through the leaves as, timbered on either side, we ascend with the valley mostly hidden from view. With the thick marches of trees conspiring to keep our destination a secret from us, and the way winding round the natural depressions and inclines of the land, our business is simply the path, the bank with its hospitable roots, the tangle of which wasps and other creatures have made homes in, and keeping a weather eye on the sheer treed drop to our left. At the same time I am attentive to the minutiae of life around me. Sunlight catches at the clapping wings of a speckled wood butterfly, charmed out of hiding by the promise of late-summer warmth on its wings. Finally it settles on balsam. How majestic it seems, propped up on its forelegs, its abdomen flush to the leaf, its wings spread to their openest extent, as though presenting itself for the sun’s inspection. There is deep contentment in its manner. Speckled woods habituate stands of oak in particular.

Attuned to one another’s particularities of gait and tolerances of various gradients, we pitch and slow in silent allowances for each other as we go; as the ravine cuts a little deeper and we climb a little higher; our lungs are tired bellows at labour. The river Wharfe is a constant clamouring companion and we cannot help but let our gazes fuss at it as the path moves us inexorably up and away from its noise. Exerting its magnetism, it draws our eyes downwards between the breaks in the trees, thundering to be heard. On top of the view – on top of the world – we admire the silken silvered ribbon of the river below as it winks and glows between the trees. More and more of it will be revealed over coming weeks as the trees lose their leaves to its flashing flow. The river stretches wet fingers as it goes to creep up rocks, slip over pebbles, and catch at leaf and branch to bear them seawards.

Sessile oaks abound in Strid Wood and autumn is inaugurated in them in strange ways. With none of the haste of the ash, which discards its leaves prematurely and greenly every year, the oak blots its leaves with yellow blisters as though stricken; the edges of the blisters blacken, or in some cases red and orange touch it to lend more of autumn colour to its decay. Over weeks of weathering the blisters increase until gradually the whole leaf is taken over by motley colours, and even then it is slow to fall away. It is a haphazard kind of autumning. More often it is the twiggy bracts – this year’s growth – that fall off in winds and weathers, taking the reluctant leaves with them. I see only a few fallen oak leaves on the path; many more are the acorns whose surprisingly loud drops are an integral part of the forest’s chatter at this time of year.

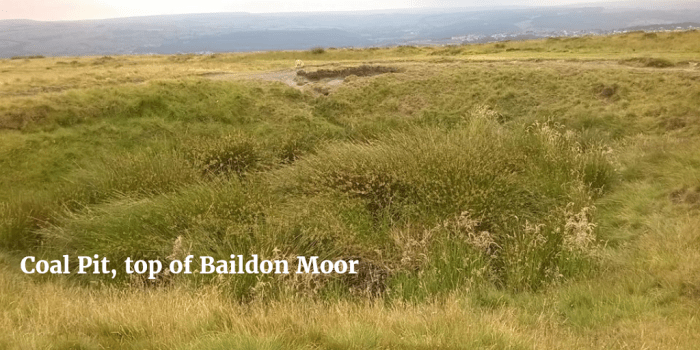

The river Wharfe is parented in Langstrothdale, its source the shake holes of the Yockenthwaite and Horse Head Moors. The narrative of the river is one of increase and drama: from shake hole springs to becks, from becks joined to form hill streams, from hill streams converging into the river. The name Wharfe derives from the Old English weorf or the Old Norse hverfr meaning winding river. And it does wind in an almost leisurely manner through its deep dale valleys, turning back on itself, noosing and curving with serpentine, sinuous skill. Until the section called the Strid between Barden and Bolton Bridge. Here it kills.

Strid is a name derived from the Old English stryth, meaning strife or turmoil. It is the section of water where the river tightens its belt and cheats its volume into a squeeze that’s sized only a pace wide. Here the pace of the river grows faster, the momentum greater, as it twists and dashes itself down the ravine.

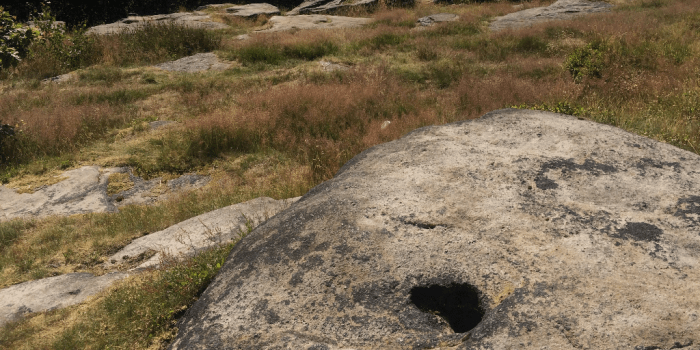

We arrive at last at the water’s side. On the bank’s sharp brink of rock I cram myself into this moment by the water, let it throb in my veins. The river is both drama and danger; people have died here. Perversely quicksilver and beautifully terrible. Its breath is in the air and on the moss-fringed rocks that suck thirstily at it. These rocks that line its passage have been scooped out and undercut by it in smooth crescents as it gushes downstream. A treacherous combination seam of fluid and organic matters colliding. The scalloped edges have their secret pools and hidden depths between. They say that it is 9m deep just here, carving out the limestone shelf beneath it, and the undertow strong enough to keep an Olympic swimmer under. The Wharfe has narrowed too quickly from its 30ft width higher up the ravine to this narrow stretch of the Strid. My gaze cannot rest for long on the water without being pulled upstream to the source and thunder of the course over its rocky bed.

I dwell for a while in a micro world: I pick a bubble to follow but it’s futile and I lose it; a single leaf falls slowly and with the grace of a bird; the greenest moss I’ve ever seen tickles the tips of my fingers. I let Autumn with all its burning majesty pass through me as the woods exhale their leafy crop on long-held breaths and the river blows out its fury.